This page contains the foundational information about childhood apraxia (CAS) of speech for families who are at the beginning of their journey. Answers to those important first questions as well as detailed information and resources about assessment and treatment of CAS are found here!

Intro to Childhood Apraxia of Speech

What is CAS?

CAS is a neurological disorder that affects a child’s ability to plan and sequence the movements needed to correctly produce words and sentences. Find a CAS Characteristics Checklist in this section.

How is CAS Diagnosed?

A trained speech-language pathologist (SLP) observes how a child performs on various speech production tasks to differentiate CAS from other speech disorders and provide a diagnosis.

Prognosis?

Each child with CAS is unique and how quickly they learn to talk is dependent on several variables.

Glossary of terms

Have you heard a word or acronym that you are unsure exactly what it means? This list explains terms that are commonly used by doctors and speech-language pathologists as they talk about CAS and other related disorders.

The Difference Between CAS and Other Speech Disorders?

CAS is different from other speech disorders in the features we see and in how it should be treated by the speech-language pathologist.

What Does it Look/Sound Like?

Each child is different, but there are some common characteristics.

What Causes CAS?

Most of the time, we do not know why a child has CAS, but new research is showing genetic links as a cause for some children.

How is CAS Treated

There are several options for treatment programs which target specific skills children need to work on during their apraxia journey.

How to find an SLP

It is very important for a family to find the right SLP who fits their child’s personality and who is trained to provide assessment and treatment for CAS.

Teletherapy

Teletherapy has become a viable option for treatment of CAS for some children.

Is This Treatment Right For My Child?

What questions should a parent ask to determine if a treatment would be appropriate for their child?

Home Practice

Should your child practice words outside of speech therapy?

Co-occurring Disorders

CAS is often accompanied by challenges in other areas of development and learning.

Advocacy

Tips for advocating for your child.

What is AAC?

Augmentative/Alternative Communication should be considered in young children who are not able to communicate throughout their day.

Socio-emotional Affects on Family

CAS affects more than the ability to say a word; it affects the child’s life including their family.

What is CAS?

When to be Concerned About a Child’s Speech

This checklist contains CAS characteristics at different ages that parents who are concerned should download, fill in and share with their health care or service provider.

What is Childhood Apraxia of Speech?

Childhood apraxia of speech (CAS) is a neurological disorder in which the child’s brain has difficulty planning and programming the movements needed for speech. The child knows what they want to say, however, the words do not come out correctly. Speech is a motor act just like throwing a basketball, hitting a tennis ball with a racquet, playing a piano, or writing a word with a pencil. In order to do a motor act, the brain must first develop a plan to execute, send the plan to the muscles to move, and then the muscles move and the act is carried out.

ENTENDIENDO EL DIAGNÓSTICO DE APRAXIA DEL HABLA INFANTIL

Ha habido un aumento tanto en el número de niños diagnosticados con Apraxia de Habla Infantil como en el conocimiento que tenemos sobre el tema. Como guardián o padre, puede ser sumamente difícil el entender qué es la Apraxia del Habla Infantil y cómo seguir adelante. Viendo que su niño/a es incapaz de articular claramente palabras que ellos saben y entienden, puede ser extremadamente frustrante para los padres o guardianes del niño/a. Este seminario le proporcionará el conocimiento que es necesario para entender mejor lo que le está ocurriendo a su niño/a con Apraxia del Habla Infantil. El comprender los déficits que subyacen, le proporcionará herramientas para poder asegurarse de que su niño/a obtenga el tipo de intervención que necesita para progresar en la adquisición del habla.

Childhood Apraxia of Speech 101

An hour long, parent friendly introduction to the characteristics of CAS.

Definitions and Descriptions of CAS

Dr. Edythe Strand, Emeritus Professor and Consultant, division of Speech Pathology, Department of Neurology, Mayo Clinic, provides a complete description of CAS. The nature of the neurologic deficits that may be involved are discussed, and terms related to CAS such as planning and programming for speech and proprioception are described.

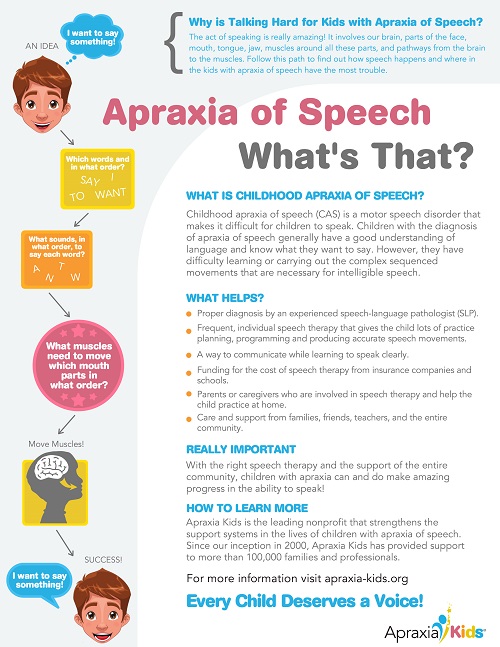

Apraxia of Speech:

What’s That?

This download explains why talking is difficult for children with childhood apraxia of speech.

There are some key characteristics that help your child’s therapist make the diagnosis of CAS. Of these, three are the most agreed upon by experts.

How is Childhood Apraxia of Speech Diagnosed?

Childhood Apraxia of Speech (CAS) is difficult to accurately diagnose and should be evaluated by a speech-language pathologist (SLP) who is trained and has experience assessing and treating children with CAS. An SLP will look at how well the child understands language (receptive language), how the child uses language (verbal and non-verbal) for communication (expressive language), and the child’s oral motor skills (how the mouth moves in general), motor speech skills (how the mouth moves for speech production), and speech melody or intonational patterns (prosody). They should also look for areas of strengths and weaknesses in all developmental areas. Sometimes it may take the speech therapist working with a child over a period of weeks or months to determine an accurate diagnosis. In this case, treatment should be geared towards improving motor planning skills.

Diagnosis of CAS

An hour long, parent friendly introduction to assessment of childhood apraxia of speech.

A journey of diagnosis explained by Sharon Gretz – one of the co-founders of Apraxia Kids (originally named Childhood Apraxia of Speech Association of North America (CASANA)) in 2000.

Do not be dissuaded from pursuing an evaluation by a speech-language pathologist if you are worried about your child. If YOU are concerned then you should pursue it. Many well-wishing and good-intentioned friends, family, and physicians may try to minimize your worries. My personal favorite was always, “You know, Einstein didn’t talk until he was four.” (Sigh.) Listen to your instincts about your own child. If nothing else a comprehensive speech/language evaluation will ease your mind and truly tell you if it is nothing to worry about. And don’t forget that speech pathologists are human and can be wrong. If you have already had your child evaluated and were told not to worry, yet your child does not seem to be progressing on his own, then pursue a second opinion. Additionally, if your child is currently in speech therapy but does not seem to be progressing, you may want to have another speech pathologist take a look.

A speech-language pathologist is the type of professional who is trained and qualified to evaluate your child’s speech and language development. As much as some other professionals have to offer (i.e. pediatricians, neurologists, psychologists, etc.), they do not have the special training and background in speech and language pathology that is necessary for the evaluation and diagnosis of speech/language problems. You should not rely on them to determine your child’s speech and language problems, although they can offer helpful information and referral. In the case of suspected apraxia of speech, parents will want to secure a speech language pathologist who has experience in the diagnosis and treatment of motor speech disorders or oral-motor functioning. Be prepared to request the evaluation be done with someone who has this experience. Do not hesitate to ask someone this question!

If at all possible, interview speech language pathologists and select someone to evaluate your child. I have nothing against new and/or young speech therapists, however, my thinking is that I want someone with solid experience to evaluate my child. Don’t hesitate to ask the evaluators about their credentials (go for at least a Master’s level with Certificate of Clinical Competence- CCC); and their experience (both in length of experience and population they have served). Children should be evaluated by clinicians who work with children! Also, if you suspect that your child may have apraxia of speech, ask the evaluator about their experience in diagnosing and treating children with this condition. Sometimes it is not possible to personally select someone, but I recommend still interviewing the person ahead of time.

Your goals could be answered by the question, “what do I want to know about my child upon completion of the evaluation?” Have goals for the evaluation and make sure those goals are communicated clearly to the evaluator ahead of time; that the evaluator understands your goals; and that the evaluator feels they can address those goals. An example is that when I took my son for a comprehensive evaluation, by phone and ahead of time, I told the evaluator that I wanted to know specifically why my son couldn’t talk (etiology); what was the name for his problem (the diagnosis); what could be done to help him (recommendations for treatment); and what kind of progress could be expected for Luke if he received appropriate treatment (prognosis). A good evaluator will most likely make a point of asking you your goals for the assessment, but regardless, don’t hesitate to speak up and offer them. I suspected that something had been missed by his early intervention therapist and so I arranged for a private evaluation.

NOTE: It is not always possible, even for the best of evaluators, to draw firm conclusions on diagnosis. Speech and language is extremely complex. The evaluator may need to go with “hunches”; recommend further specific evaluations by another person; or recommend trial therapy to try out their “hunches”. This can be frustrating but you should know it is a reality.

Your input in the evaluation process is extremely important. The younger the child, the more the evaluator will need to rely on your observations. It could be helpful to make a list of things you have noticed to take with you to the assessment – perhaps things that have made you worry. Write down your questions to take with you as well so you don’t have to rely on memory. Take a list of sounds/words or word approximations your child produces and what they mean. Additionally, many speech pathologists will welcome audio/video recordings of your child. This can be especially beneficial if your child does not verbalize to his potential in the evaluation setting. With older children, the evaluator will hopefully be able to elicit direct samples from them.

Child Apraxia Treatment

The Child Apraxia Treatment webpage has evidenced based information for parents and training for professionals on assessment and treatment of CAS including the Dynamic Temporal and Tactile Cuing therapy protocol by Dr. Edythe Strand.

Prognosis

What Will the Future Hold?

After receiving a diagnosis of childhood apraxia of speech (CAS), parents have so many questions and worries about what the future will hold for their child. Getting a picture of that future is challenging at best, as there is no longitudinal research to give clear answers for any particular child and every child’s journey with apraxia is different.

Glossary

Glossary of Terms for Childhood Apraxia of Speech

Childhood apraxia of speech (CAS) is the current preferred terminology to describe the disorder. Other terms still in “use” and from the relatively recent past include “developmental apraxia of speech” and “developmental verbal dyspraxia”. Use of the descriptor “developmental”, however, unfortunately provides a false implication to other professional groups and insurance reimbursors that the speech difficulties of affected children are akin to “delays” in development; are transient and can be simply outgrown without direct intervention.

The use of the prefix “A” (i.e.: absence) and “dys” (i.e.: partial) attached to the root word praxis may also provide confusion. In most instances, use of either of the terms apraxia or dyspraxia appear to be based on personal preference, one’s graduate educational institution, and/or one’s geographic location rather than a meaningful or practical difference. The term apraxia, however, is the choice used nearly exclusively to describe the adult form of the disorder. Praxis, in either case, refers to “skilled movement.”

What is the Difference Between CAS and Other Speech Disorders?

There are many reasons that children may not be developing age-appropriate speech and/or language skills. Some children experience a developmental delay of speech – their speech is following a pretty typical path of childhood speech development, although at a slower rate and often commensurate with cognitive ability. Other children experience one of several specific speech and/or language disorders in which their speech is “off track” and not developing on a delayed course. For example, when a child has difficulties producing a particular sound or just a few sounds that their peers are already saying, it is called an articulation disorder (e.g., a lisp). A child who has a phonological disorder simplifies their speech and has difficulties producing a family of sounds that have traceable patterns (e.g., a child that produces the back sounds like k and g in the front of their mouth, substituting the sounds consistently with t and d respectively). A child with a diagnosis of dysarthria has weakness, paralysis, or incoordination of the muscles needed to speak causing poor speech intelligibility. Childhood apraxia of speech is a neurological motor speech disorder where the planning and programming of movements for speech are disrupted. Childhood apraxia of speech is not a developmental delay of speech. It is a specific type of speech disorder and is not likely to improve without properly tailored therapy. A speech-language pathologist with knowledge and training in CAS can make a differential diagnosis which is crucial to receiving appropriate treatment.

Revised November 2021

What does it look/sound like?

This young girl displays several characteristics of CAS. She has vowel errors and has difficulty sequencing the longer syllables of balloons and ice cream shown by prolonged sounds and omission of a syllable and choppiness in the phrase “cake is not hard to me”.

What Causes CAS?

Parents should be reassured that speech difficulties are not caused by common parental worries such as sending them to day-care or alcohol consumption during pregnancy. Children do not have CAS because of a parental separation or because the family moved to a new city. We are learning more all of the time about the causes of CAS.

The Genetic Bases of CAS: A Clinical and Parent Perspective

Dr. Angela Morgan, a researcher in the area of genetic links for CAS, discussed the history and basic terminology of genetic testing and research results from past and current studies. This research leads to targeted therapies and improved outcomes for children. Haley Oyler provided insights learned during her genetic testing journey which led to a diagnosis for her son who has CAS.

Genetic Testing and CAS

Around one third of children with CAS have a genetic cause for their condition [Hildebrand et al., 2020]. New genetic technologies now enable rapid and relatively cost-efficient genetic testing. This has led to the discovery of many new genetic conditions associated with CAS.

How is CAS Treated?

Therapy for CAS should look different than treatment for other types of speech sound disorders. There are several evidenced based treatment programs which target specific skills children need to work o during their apraxia journey. Which program to use is decided on the age and current abilities of the child. But there are some underlying principles that are the same across most treatment programs such as use of the principles of motor learning and use of some type of cuing hierarchy.

Principles of Motor Learning and Childhood Apraxia of Speech:

A (hopefully) Gentle Introduction

This introductory presentation by an expert researcher will explain important concepts in motor learning and some principles that may enhance speech outcomes for children with CAS. An understanding of these concepts and principles may help parents better understand the choices and procedures implemented by their child’s SLP.

How is Speech Therapy Different for CAS?

There are several types of disorders which cause a child to be difficult to understand, including childhood apraxia of speech, and the treatment for each one is different. One type is an articulation disorder where the child only has a few sounds they are unable to produce correctly (‘r’, ‘s’, and/or ‘z’). In therapy for an articulation disorder, children work on improving each single sound one at a time and generally start with producing the sound in isolation before they work on words with the sound in a specific place in the word (at the beginning of the word). As the child masters the sound at the beginning of words, treatment moves into producing the words in phrases and then sentences and finally in spontaneous speech.

Key Factors in Speech Therapy for CAS

Childhood apraxia of speech (CAS) is a motor speech disorder that affects a child’s ability to plan the movements needed for talking. Motor learning for speech occurs in a very similar way to the motor learning required for tying shoelaces, shooting a basketball, or hitting a golf ball with a golf club. The principles and theories that help us understand this learning process are called “Principles of Motor Learning”, and should be the guiding factor in speech therapy for children with CAS.

Therapy with a young child with CAS

In this video, the therapist is working with the child on getting correct production of the word “maybe”. She is directly in front of him with his hands on her face to keep his attention focused on the visual cues of her mouth. She starts with direct imitation and provides cues and feedback on his production to help him. When he still struggles to get the intimal /m/ sound, she uses simultaneous production to get it correct.

Child Apraxia Treatment

The Child Apraxia Treatment webpage has evidenced based information for parents and training for professionals on assessment and treatment of CAS including the Dynamic Temporal and Tactile Cuing therapy protocol by Dr. Edythe Strand.

Treatment of CAS

An hour long, parent friendly introduction to the treatment of CAS.

How to Find an SLP

What to Look for in an SLP

What training does an SLP need to have to diagnose and treat my child with apraxia? Where can I find an appropriately trained SLP? What questions should I ask an SLP who might be treating my child? Find the answers to these questions in the full article below.

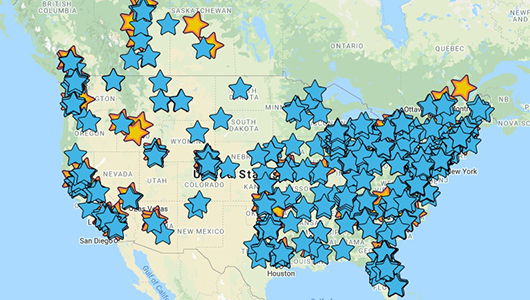

Speech-Language Pathologist Directory

At Apraxia Kids, we understand how very challenging it can be to locate a speech-language pathologist who has a reasonable level of experience and skill in evaluating and treating children with apraxia of speech. For that reason, we have created an online directory to connect families with SLPs across the U.S., Canada, and beyond who have shown an understanding of and experience in treating children with apraxia of speech.

How to Find a Speech-Language Pathologist When Your Child Has Apraxia of Speech

This handout identifies questions and issues for parents to consider when locating an SLP for their child and also has suggestions on where to locate experienced SLPs.

Teletherapy

Telepractice is the application of video technology to the delivery of speech language pathology and audiology professional services at a distance by linking clinician to client for assessment, intervention, and/or consultation. Telepractice is recognized by the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA) and supported by research as an effective modality to conduct services. It can be used to directly engage the child in therapeutic activities or to provide coaching to family members for how to work with their child on their objectives. The family and therapist should decide what is best for each individual child.

Many speech-language pathologists are offering alternative methods to provide children with therapy at a distance because of the need for virtual services during COVID. It has now become a viable option that will continue to be used in the future.

Teletherapy and CAS

SLPs and families alike have been challenged with treating children with CAS via teletherapy. What does teletherapy look like, what are the SLPs and parent roles and is it worth our time? How can we make this work with our kids with CAS? We will discuss ways to make teletherapy worthwhile when our options are limited.

Is This Treatment Right For My Child?

How can you know if a treatment or program is right for your child? What questions should you ask? Is there evidence or research to show it works? Learn here how to make these judgements for treatment programs!

Judging Evidence Explanation and Glossary

Read about some important things to consider when evaluating research evidence.

Would This Program Be Good For My Child?

As professionals and concerned parents/caregivers, we are constantly bombarded with information. Some is fact-based, some more anecdotal, and some just opinion. Often, we are left with more questions than answers after hearing or reading about some program or treatment option. That is a GOOD thing!

Whenever you are researching if a specific program or treatment is right for your child, consider these specific questions you should ask yourself.

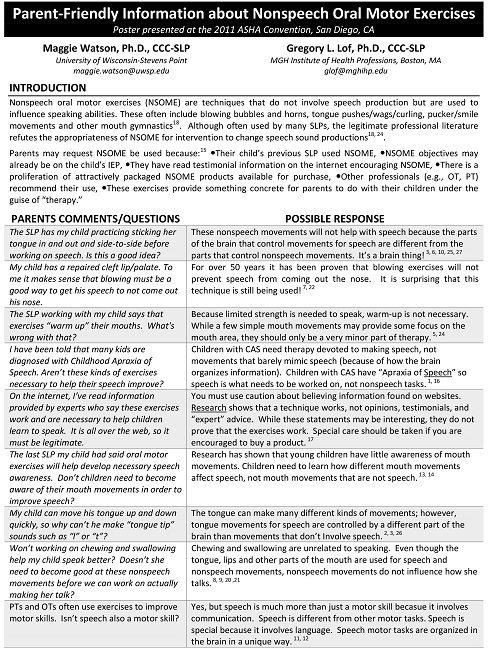

Information about Non-speech Oral Motor Exercises

The use of Nonspeech Oral Motor Exercises (NSOME) has received a great deal of attention in the field of Speech Pathology over the years. Dr Gregory Lof has been at the forefront of this and has shared an article with Apraxia Kids.

Home Practice

Home practice is an important part of the therapy process for a child with a severe speech sound disorder such as CAS. Your child is only with their therapist a short time each week and practice outside that time will increase the amount of progress the child makes. Your child’s therapist should be giving you words to practice at home that they are able to easily say or activities to reinforce skills learned in therapy.

Taking Advantage of All Those Teachable Moments:

Speech Therapy at Home For Young Children with CAS

Parents and caregivers are critical to enhancing success for children with childhood apraxia of speech. This webinar by an expert clinician will focus on strategies and activities as part of home practice to improve your child’s rate of progress, provide the opportunity to generalize their targets, and build self-esteem that results from feelings of success and improved speech clarity.

Keep Calm and Chatter On

Parents have busy schedules and with the addition of practicing “speech words”, things can become even more hectic. This was multiplied with all of the changes that occurred during the pandemic. A CAS expert has great ideas about ways to incorporate speech practice throughout the day that is appropriate all of the time.

Comorbidities

Childhood apraxia of speech can occur on its own, but often there are other disorders that are identified either when the child is very young, or when the child is older and other challenges are seen. Parents and caregivers need to closely monitor development in all areas – gross and fine motor, attention, academics, and socio-emotional skills as well as overall health and physical development.

You Be You

Many children with CAS have other conditions, ranging from general motor impairment, to genetic conditions like Down syndrome or 22q11, to neurodevelopmental disorders like autism and learning disorders. The most efficient approach to therapy for children with “CAS+” will involve identifying priorities based on understanding of the whole child, not just their speech disorder. This session by an experienced clinician will discuss how priorities for intervention may be considered, and how motor-based treatment for speech may be integrated into treatment for specific co-occurring conditions.

Could It Be Both? Distinguishing Between Autism and Childhood Apraxia of Speech

Parents frequently ask how to distinguish between autism and childhood apraxia of speech (CAS), or how to determine if a child with autism could also have CAS. This can be difficult to determine if the child is showing signs of both—especially if they are not yet talking very much. So, what makes diagnosing CAS among children with autism so difficult? Is a child more likely to have CAS if they also have autism (and vice versa)? Are these labels even important? How can I advocate for accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment for my child? This article brings you answers based on the best available research evidence and personal clinical experience.

The Role of the Developmental Pediatrician and Children with CAS

Developmental-behavioral pediatrics is a subspecialty of pediatrics. As such, it functions with the orientation, beliefs, and practices of Western allopathic medicine. In this tradition, the practitioner gathers information about signs and symptoms and tries to explain them through a single over-riding diagnosis. In the process, the practitioner considers many diagnoses that might account for signs or symptoms and obtains additional history, expands the physical examination or conducts tests to determine which diagnosis is the best fit. Allopathic medicine became inextricably linked to the scientific process in the early 20th century. Since then, the causes and best treatments for conditions, whenever possible, are determined through rigorous scientific study.

What other Professionals May Be Involved?

If you have concerns about your child’s development in addition to their speech, other professionals may be called on to get involved in helping your child. If there are other co-occurring developmental or medical conditions present, other disciplines will be involved as needed. For example, a developmental-behavioral pediatrician can evaluate all aspects of your child’s development.

Advocacy for Parents

As children with CAS grow up and develop, their parents and caregivers are placed in many situations that require advocacy skills. This advocacy may have even started before the child was diagnosed with CAS. Perhaps you had to advocate with your child’s pediatrician in order to receive a referral for speech-language evaluation. Receiving insurance approval for speech therapy may be the point at which advocacy from a parent or caregiver is put into play.

A Parent’s Role When a Child Has CAS

As a parent, your job is to make sure that your child is healthy and meeting developmental milestones. When we think of developmental milestones, we usually think of rolling over, sitting, standing, walking, and talking. You probably noticed that something was missing, but you couldn’t put your finger on it.

Becoming an Advocate

Becoming an advocate means becoming an expert. In the course of your journey, you need to learn all that you can about your child’s particular disabling condition and how this condition can be remediated.

What is AAC?

Augmentative Alternative Communication (AAC)

Augmentative/Alternative Communication (AAC) is using some type of different means for the child to communicate when verbal speech is not effective. There are many different types of AAC from simple to more complex means.

AAC Strategies for Apraxia

This session will provide 10 easy to implement suggestions for using AAC technology, and supports to encourage language and literacy growth in individuals with childhood apraxia of speech (CAS). Information and valuable tools about being a great communication partner will also be shared to help families and teams provide optimal circumstances for growth, literacy and engagement. AAC does not have to be presented *instead* of use of natural speech for individuals with CAS. Watch this session to learn more about the benefits of using it as a part of a whole speech and language intervention program!

Speech and Language / OT Apps

Many families ask about tablet applications – “apps” – specifically for childhood apraxia of speech. Please know that apps should be used with therapist and parent supervision to support the child’s speech practice or to assist them in their communication attempts. Some apps are for speech practice while others are for providing an augmentative/alternative communication tool.

Why are so many families pursuing tablets and apps for their children with apraxia? For a number of reasons – that many children are quite fascinated and engaged by the interactive nature of apps and because they provide other ways to communicate what children who struggle to speak want to say and what they know. Apps can help extend speech, language and educational practice and/or can be used for motivation and reinforcement for practice.

Socio-emotional Effects on Family

A child with CAS needs support from their entire family. There are lots of ways family members can be involved, but each family member needs to know it is a journey and there are often bumps along the way.

Family Webinars

Coping with Feelings and Emotions

No doubt if you are the parent of a child recently diagnosed with apraxia of speech, you are having many feelings and emotions in reaction to the news. You may be feeling quite fearful about the future. Perhaps you are wondering how this happened to your child or even if you did something to cause your child to have apraxia.

The Parent’s Journey

By Pamela Darr Wright, M.A., M.S.W.

Worry. Sadness. Fear. Guilt. Helplessness. Anger. Confusion. Disappointment. More worry.

Parenting has always encompassed difficult periods-times when parents feel concerned and confused-sleepless nights when they worry about how well they are fulfilling their responsibilities to their children. Raising a disabled child “ups the ante.” Meeting the complex needs of the child with a disability can be extraordinarily difficult, frustrating, emotionally draining-and expensive!

Parents of disabled children understand one crucial fact-that only by obtaining an appropriate education will my child have a real opportunity to lead a fulfilling, productive life.

Unfortunately, statistics about the outcomes of special education programs will not alleviate your concerns.

Researchers have found that most special education programs fail to confer adequate educational benefit to many of the youngsters they are designed to serve. The statistics are sobering:

- 74% of children who are unsuccessful readers in the third grade are still unsuccessful readers in the ninth grade. (Journal of Child Neurology, January, 1995)

- Only 52% of students identified with learning disabilities will actually graduate with a high school diploma. Learning disabled students drop out of high school at more than twice the rate of their non-disabled peers. (Congressional Quarterly Researcher, December, 1993)

- At least 50% of juvenile delinquents have undiagnosed, untreated learning disabilities. (National Center for State Courts and the Educational Testing Service, 1977)

- 31% of adolescents with learning disabilities will be arrested within five years of leaving high school. (National Transition Longitudinal Study, 1991)

- Up to 60% of adolescents who receive treatment for substance abuse disorders have learning disabilities (Hazelden Foundation, Minnesota, 1992)

- 62% of learning disabled students were unemployed one year after graduation. (National Longitudinal Transition Study, 1991)

A meaningful education will help turn these figures around.

“The pure rage that stems from an unredressed injury can be more fearsome than that produced by the original wrong.”

(Gerry Spence, respected attorney-litigator and commentator on civil rights in America)

John sat on the couch in my office. His face reddened and his fists clenched as he talked about his son Chris and his contacts with the teachers and administrators at Chris’s school:

“My son is 13 years old and he still can’t add simple numbers. He can’t add 15 and 9. He can’t read either, and he’s been in special ed since he was six years old.

This year they put him in regular classes with some sort of collaborative teacher-they say that’s how they teach LD kids at his school, and that’s all they can do. And now he’s failing everything-everything! Last grading period-four F’s and one D. The only thing he’s passing is Science.”

As I sifted through several inches of disorganized documents that John brought to the meeting, John continued:

And when I complained that he isn’t learning, they told me it’s my fault because I’m not making him do homework! Do you know what a nightmare homework is? He’s exhausted when he comes home from school-where he hasn’t learned anything-then he has to spend two or three hours doing papers. It’s a nightmare. A real nightmare . . .”

I continued to skim through the documents-old standardized tests, letters from Chris’ teachers, school papers, report cards, IEPs from the first grade to the present-all mixed up. No current psychological or educational testing. John’s voice raised in anger:

“Pam, you don’t understand. They lie. They blame kids for not learning when they are not teaching . . . And they are stupid. They can’t teach, they can’t do anything. They are morons! And I told the principal that when I met with him last week . . . “

Tragically, John’s case is not an isolated situation. This father’s frustrations and fears had driven him to explode and demean school personnel. His reaction – an angry outburst – gave him short-term relief from his intense feelings of frustration. Did his explosion and insults lead to the development of a more appropriate educational program for his son? Of course not. Will it be more difficult for John to work effectively with school personnel in the future? Definitely. Will Chris be the ultimate loser? You bet!

The intense emotions experienced by parents often become their “Achilles heel” as they attempt to obtain an appropriate education for their child. When the local school system fails to provide the child with that critical “special” educational experience or offers “too little, too late,” many parents are shocked and angry.

These parents feel betrayed by the one system which they had trusted to help with the difficult task of educating their child with disabilities. Once lost, trust is hard to regain. As Gordon, the father of a fourteen year old learning disabled boy erroneously diagnosed by the school district as “seriously emotionally disturbed,” explained:

One of the great tragedies of parental disillusionment is that even if we finally find a good educational program, we know that our child has been damaged by people within the school system. We don’t know how severe or enduring the damage will be. The feelings of betrayal are often so strong and bitter that there will never be any trust by the parents.

Children enter our lives with excitement, anticipation and joy. We have high hopes and great expectations for this new life. How do we process the new reality-that this much-loved child has a serious “life disability?” Or that this disability may negatively affect our child’s ability to live a productive, satisfying, independent life? Parents must mourn the loss of the “perfect child” before they can become effective advocates.

Amy is a seven-year-old child who was diagnosed with autism.

Her mother Karen recalled:

“As parents, we are at an enormous disadvantage. When we discover that our child is disabled, we are in shock and grieving. We don’t know the laws or even that there are laws. We don’t know about the IDEA. We don’t know that we have any rights. We just trust for the first couple of years. Then something happens which causes us to become a little suspicious and we begin to look into things . . . and the worms come pouring out of the woodwork.”

Mourning is the natural, necessary and healthy process that begins when you learn that your child has a disability. If not handled appropriately, the mourning process can continue for years. You need to come to terms with your loss and mourn the hopes and dreams that may never be realized.

In common with other major losses, mourning encompasses predictable emotional stages. Typically, parents move back and forth between these stages, especially in the early months and years following their child’s diagnosis.

“I don’t believe it. He is just a late bloomer. All the boys in our family had to repeat grades. And look at us-we did okay!”

Millions of adults have undiagnosed, untreated learning disabilities and attention deficit problems. If they are fortunate, they find a “good fit” in their choice of work and are successful, despite their disabilities. Yet, most learning disabled adults lead lives that are deeply affected by sadness, disappointment and frustration.

Undetected, unremediated learning disabilities are causally connected to many other serious life problems-from juvenile delinquency and substance abuse to severe marital problems, domestic violence, and chronic unemployment. Typically, learning disabled adults develop negative views of themselves as lazy or stupid-or worse.

Most of these adults-numbering in the millions-have developed a strong, pervasive sense of having failed. From their perspective, they failed to live up to their own expectations and the expectations of others. Their negative view of the self and their identity as a failure permeate all areas of life, leading to interpersonal, socio-emotional, marital, vocational, and legal problems.

If parents continue to deny the seriousness of their child’s problems, these problems will not be appropriately treated, the child will not receive appropriate educational remediation-and the child is very much at risk for becoming another tragic statistic.

Unfortunately, parents who are in denial may find willing co-conspirators within the educational system. In some school districts, teachers are under a gag order by school administrators, forbidden to share their concerns about your child or to provide you with the information that you need about the child’s lack of progress. In other districts, school administrators who have the lowest referral rates for special education services receive special commendation.

“I just wonder how the psychologists and special education directors who so systematically work to deny educational services to our kids can face themselves in the mirror every morning . . .”

Intense feelings must find an outlet, and parents of disabled children have lots of intense feelings-including anger. Typically, these parents also feel frightened, helpless and out-of-control. To assert some sense of control, they may attempt to assign blame for their child’s problems-onto school personnel, the child, their partner, themselves, God, bad luck, or fate.

To avoid feelings of guilt and sadness, some parents externalize their emotions, blaming or faulting someone or something for the problems their child is experiencing. Sometimes this blame is warranted. As we will see in Mariah’s case, when parents believe they have been betrayed by the educators in whom they placed their trust, their anger and sense of personal outrage can be intense.

Mariah is a nine year old child with at least average intellectual ability. When she was two years old, a brain tumor was detected. Over a period of years, Mariah endured painful surgeries, chemotherapy and radiation therapy. These treatments saved her life, but left her with multiple challenges, including learning disabilities, orthopedic and speech problems, and an attention deficit disorder.

Mariah’s school district offered to provide a minimal level of special education services to this child. First, by using a “discrepancy formula,” they refused to provide any special education services aimed at remediating her learning disabilities, claiming that she had not fallen far enough behind to qualify for services.

Later, using a novel argument, they argued that Mariah was not eligible for services under a “Traumatic Brain Injury” classification because her brain injury was caused by a tumor, not “acquired” from an external injury. Not surprisingly, Mariah’s parents were shocked and angry.

Mariah’s mother, Elizabeth, spoke of her two year battle to secure appropriate special education services for her daughter:

“I wake up in the morning and begin making phone calls. The laundry sits along with other relics of normal life. The school district is so good at what they do-setting up roadblocks and denying educational services-that it is consuming my life just to get an IEP for my daughter.

I didn’t know how the system worked for the first couple of years. I just kept going from place to place, getting evaluations which I gave to the school. I thought that once they understood what Mariah needed, that would be it. Was I ever wrong! All those evaluations were just “filed.” Period!”

Elizabeth’s soft voice held a strong undercurrent of contempt:

“When I sit and think about the undeniable fact that my child was not provided with an appropriate education for years, not as a result of “blundering” or “poor judgment,” but intentionally, and that we were manipulated by intentional double-talk, my blood just boils.

Why is this type of thing different from any other scam? If school district personnel deprive children of their legal rights through the use of double-talk, flimflam, fraud, deception . . .this should be a crime under the law, and they should be held personally responsible for their actions!”

Some parents are angry about the hard choices-and the sacrifices-that must be made. That these choices and sacrifices are often difficult, is attested to by comments made by the father of two disabled youngsters:

- Both parents being able to work in their fields, or one having to stay home because the children’s needs are so great.

- Having to choose between one kid getting mental health care, or the other kid getting speech therapy.

- Being in crippling debt, or merely being in tremendous debt.

- Losing a retirement fund that was built up over 24 years or losing a college fund that was built up over 17 years.

- Having to choose between a psychiatrist or a psychologist solely on the basis of cost.

- Having to choose between marital therapy for the parents or bankruptcy.

Tough choices.

Other guilt-ridden parents internalize their feelings, turning their anger inward and blaming themselves for the child’s problems. Anger turned inward leads to depression. And depression, with attendant feelings of inadequacy, helplessness and hopelessness, leads to emotional withdrawal.

A tearful young mother sat across from me in the office. Kim’s nine year old son Justin had been diagnosed with a learning disability in reading and language (i.e. dyslexia) and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) nearly three years ago. Now in the fourth grade, Justin continues to have great difficulty reading, despite having received three years of special education services.

Justin’s temper outbursts at home had intensified-the family dreaded the frequent rages during which he turned his anger on himself and family members. His mother was overcome with feelings of guilt, inadequacy and depression. She saw a psychiatrist who had placed her on antidepressant medication.

Kim had experienced similar problems in school. She reversed letters and syllables and “read from right to left” for many years. As an adult, her dyslexia was diagnosed. Kim’s school failures had induced in her a pervasive sense of shame. Unlike her son, she became overtly withdrawn and depressed.

Kim’s own complex blend of personal history and emotions had created a compulsive need to apologize-for taking up my time, for not understanding what various educational tests measured, for being depressed, for being a “bad Mom.”

Based on the results of Justin’s earlier evaluations, which clearly identified his dyslexia, coupled with his ongoing inability to decode words, I urged Kim to contact her son’s school. Justin was in need of a more intensive program of remediation.

Kim requested the meeting, which was also attended by the principal.

That afternoon, my answering machine contained a lengthy message from Kim:

“Pam, I had the meeting. They were really mad at me. Justin’s LD teacher kept telling me that she gave Justin extra time and that she worked really hard with him. She even permits him to sit in the front of the room. I felt bad. I told her that I really did appreciate what she was doing for Justin. I told her over and over that I knew she was doing everything she could for him. I think I need to meet with her again . . .

When I told them that you thought Justin needed more testing about his dyslexia, they got upset. They asked me why I was talking with you. It’s like they felt that I didn’t trust them or something.

When I tried to talk about Justin’s dyslexia, the principal sat back in his chair and rolled his eyes. The principal and the LD teacher started talking and laughed. I know they were angry. I wanted them to know that I really appreciated everything they were doing for Justin, it wasn’t that I was ungrateful but . . .”

Remember John and his son Chris, earlier in this article? John’s inability to control his anger and frustration caused him to react in a way that would have negative consequences for his son Chris. Like John, Kim approached the school to request additional services for her child. What are your thoughts about Kim’s approach?

Like John, Kim’s emotions are her Achilles heel. Unlike John, Kim is a conflict avoider – polite, unassertive, afraid of authority figures, and terrified that she will anger or offend others. By being conciliatory, is Kim functioning as an effective advocate for her son? Are the school personnel at Justin’s school likely to accede to her request for additional testing? Has Kim persuaded the school officials to develop a more intensive program to effectively remediate Justin’s dyslexia?

Sadness is a normal part of the mourning process. Guilt, sadness and regret often merge into a painful tangle of emotions. In Justin’s case, his mother’s feelings of shame about her own learning disabilities and her lack of self confidence, combined with her pattern of conflict avoidance, made her an ineffective advocate for her child.

Many parents try to avoid experiencing feelings of sadness and regret, preferring to remain angry. Given the pain inherent in sadness and regret, this is an understandable impulse. Yet, it is essential to mourn the loss of the “perfect child.” Mourning the loss is not the same as repudiating your child or finding him less worthy of your love. Instead, it is part of the process of acceptance and resolution which will free you to move on.

THE INTIMIDATION FACTOR AND TRANSFERENCE

At a parent support group meeting, I listened to the following exchange between two fathers. Both men had children with learning and attentional problems.

The first father, a businessman who specialized in marketing and sales confessed:

“I always feel anxious and intimidated when I go to school for a meeting about my daughter. I start to feel anxious before I even get there. By the time I get to the parking lot, my stomach is in knots. I feel completely intimidated. When they ask me what I think, I don’t know what to say. Being speechless is usually not a problem for me!

I know my daughter is not learning. I know she is falling further and further behind. I know that I’m very worried about her, but I don’t know exactly what they need to do I’m not a teacher. I don’t know what to say-aren’t they supposed to be the experts?”

The other father, a respected physician and father of two children with disabilities, responded:

“Boy! Do I know that feeling well! There is something about the process-this team business where you sit around a table and it’s just you, the parent, on one side, and six or seven school people on the other. I always feel intimidated when I go to a meeting at the school.

I feel like I did when I was about eight years old and had to go to the principal’s office. was in big trouble then and I feel like I am in big trouble now!”

People are intimidated in different situations and contexts. Many of the decisions made for handicapped children are made by “teams” or committees. It is not unusual for IEP meetings to include five or six-or more-school district representatives-and one parent. In addition, these meetings are held at the school-unfamiliar ground for most parents. Given these dynamics, it is not surprising that most parents feel intimidated.

And how do people respond when they feel intimidated? Some respond with anger and defensiveness. Others wilt under the pressure.

If the parent also had difficulties in school, old negative memories and emotional reactions will often color his or her present feelings about schools, teachers, authority figures, and school meetings. The transference of emotions from past situations to present circumstances occurs in all areas of our lives. This transference can be positive or negative.

Remember Kim? Because her dyslexia was undiagnosed and unremediated, her personal experiences in school were predominantly negative. These past experiences led to negative expectations-which contributed to her fearful, conciliatory responses toward the “experts” at her son’s school.

However, if the parent experienced school as a helpful, supportive place, then positive feelings and expectations will tend to transfer to the current situation. These parents expect that the school will be a helpful environment for their handicapped children.

GETTING “STUCK”

Because the mourning process involves intensely painful emotions, many parents try to avoid it by minimizing or denying their feelings. Others get “stuck” in one phase-and fail to complete the process.

Like people who see themselves as “victims” of divorce, these parents remain angry, bitter, guilty, or depressed for years-or for life. Mired in negative emotions, they accomplish little of value for their child. You must not let this happen to you.

Failure to deal with reality causes other problems. As we have seen, when parents remain in denial and refuse to acknowledge that the child’s problems are serious, their child will not receive necessary educational services. Parents who obsess about the transgressions perpetrated by the school system often “burn out” without achieving anything that is of true value to the child.

However, there is another serious danger that many parents of disabled children face. Little has been written about this danger in the parenting and advocacy literature but it is of great concern.

OVERPROTECTIVENESS

Attempting to suppress feelings of personal guilt and external blame, many parents become overprotective of their child. Unable to protect the child from the disabling condition, they attempt to protect him from other difficult or challenging areas of life.

The development of overprotectiveness, fueled by pity and guilt, may be the biggest mistake that any parent can make in raising a child with a disability. Overprotective parents unwittingly create chronic dependency and “learned helplessness” in their children-a mindset that will often persist throughout that individual’s life.

These children grow up to be adults who believe that they “can’t” do things. Let’s look at the case of Paul. Paul is a young man who was diagnosed with learning disabilities while a young teen. He received special education assistance and finally graduated from high school.

After being fired from dozens of jobs over a period of years, Paul enrolled in a community college where he took a night course. To his surprise, he was successful.

Encouraged by his unexpected success, Paul returned to college and, after several years of part-time study, graduated from a four year university with a degree in special education. Paul had decided to become a special education teacher.

Paul’s teaching career had its ups and downs. He spent several fairly successful years in a small rural school system. Open about his learning disabilities, he asked for and received help from other teachers. Eventually, Paul obtained a job in the large urban school district where he had received his own education. He would be teaching elementary school children who had learning disabilities. He had achieved his dream.

But Paul had other problems which caused his dream to self-destruct. Pampered by over-protective parents, Paul had developed a personality style that was characterized by helplessness and a stubborn insistence on getting his way, coupled with a lack of empathy and an inability to see the perspectives of others. Paul firmly believed that his learning disability meant that he could not do certain things.

In his new teaching position, Paul was expected to teach children all academic skills – from reading and spelling to math. Paul’s learning disability was in the area of math. Despite his disability, the principal expected him to teach math. Paul refused. He also refused to accept help from an experienced LD teacher who offered to help him learn the necessary math skills. Paul’s response was, “You don’t understand. I’m learning disabled. I can’t do math.”

Eventually, Paul was terminated from his position. He moved back home with his elderly parents. His dream was dead.

Grief Associated with Disabilities

There is a complex grieving process that many parents experience when their child receives a CAS or other diagnosis. Dr. Iuzzini-Seigel and Laura Smith will introduce definitions and the stages of grief that are common to this grieving process and will discuss strategies to keep moving forward in a positive way.